Feeding the Food Insecure

Growing up as a child and teenager, my family would have been classified as economically disadvantaged because we qualified for free lunch. Shopping as a family in thrifts stores and having clothes donated to us was viewed as normal. Receiving the government monthly checks, along with the blocks of cheese, bread, etc., fed our family of nine. Whenever there was a shortage, other family and friends always helped us out, so we were never hungry, in need of clothing or lacked adequate shelter. So we were always able to come to school with enough sleep and nutrition to learn without challenge. Have you ever gone to bed hungry, because there was no food in your house? As parents, leaders, and educators, it is one of our greatest fears to see our children hungry. However, some children do unfortunately suffer from food insecurity.

Photo by Mick Haupt on Unsplash

Food insecurity is, “limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to gain acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways.” Unfortunately, many children who face food insecurity are often physically, emotionally, and cognitively behind their food-secure peers. Food insecurity can severely affect children’s health and brain development long before they enter a classroom. That is why leaders and educators need to ensure all of their pupils are food-secure. Addressing food insecurity in your institution will help foster equity in your community. When all children are food-secure, they all have a better chance at success.

Food insecurity has a direct impact on the health of your pupils. The most affordable food is often the unhealthiest, especially in food deserts, where finding healthy food at an affordable price can be difficult. Because of this, food-insecure households are much more likely than food-secure households to report eating unhealthy foods. It also affects a child’s education. Food-insecure children often show smaller gains in reading and math comprehension than their food-secure classmates. Food-insecure children and teenagers have been shown to miss school more frequently, and are more likely to repeat a grade than food-secure children. Any disadvantages in which food insecurity puts some children also points to inequity in your organization.

Photo by RODNAE Productions

So, how can we eliminate food insecurity in our educational institutions? School breakfast programs are a great option. Programs like this help decrease the time between meals for children with limited access to food outside of your institution. School breakfast programs have shown to increase attendance, decrease tardiness, and provide quality nutrition to students who might not always have access to a healthy breakfast. The same goes for lunch and after-school meal programs. Lunch programs are pillars to ensuring the food needs of your students are met. After-school programs help ensure children get in one more meal before returning home, where they might not have sufficient food to eat for dinner. We can often reimburse many of these programs, and they are an equitable investment to make in your educational institution to ensure your community is food-secure.

Leaders, food insecurity doesn’t stop with the students. It can also affect your educators. Food insecurity affects the health of your educators, as well as workplace productivity. Employees that are food-insecure are more likely to miss and be distracted at work. Time lost when employees are absent or not fully productive comes at a cost, not only to your educational institution but also to the students and their learning experiences. In order to foster a healthy, productive work environment, access to safe, nutritious food is essential.

Photo by RODNAE Productions

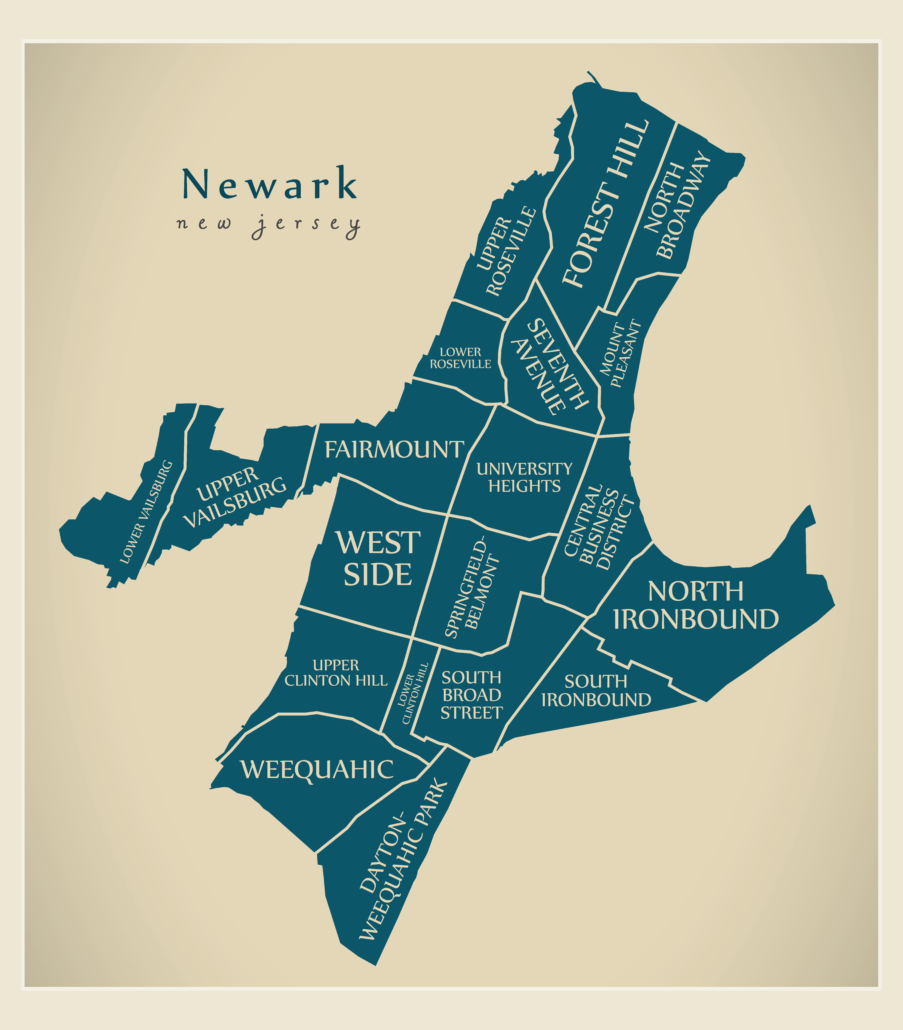

Combating food insecurity in your educational community is a keyway to help foster equity among your students, as well as your educators. Providing meal programs to your community is just one great way you can ensure everyone stays alert and productive while teaching and learning. Have you identified food insecurity as an issue in your educational institution? GOMO Educational Services can help you do that, and more. We perform equity audits on educational institutions and organizations, and then we use the information we gather to help you change your community so that everyone benefits from the resources they need and are better poised for success. Don’t know where to start? Contact us today for guidance!